Visit any place: a town, a school, a neighborhood, a college campus, even a restroom, and you will see telltale signs of the culture that lives there in the details that surround you. The trick is noticing. Here are images of details some may or may not notice when traveling in China. Each gives rise to some possible revelations about China– and raises some questions to ask about the culture in the place you call home.

Visit any place: a town, a school, a neighborhood, a college campus, even a restroom, and you will see telltale signs of the culture that lives there in the details that surround you. The trick is noticing. Here are images of details some may or may not notice when traveling in China. Each gives rise to some possible revelations about China– and raises some questions to ask about the culture in the place you call home.

This lady was carefully dusting every opening of a rooftop railing inside a garden in Shanghai. As tourists and other visitors walked beneath her, she continued cleaning. I immediately thought of the people we had seen sweeping the side of major highways with brooms. What might this possibly say about China’s employment or interest in cleanliness or care of public areas? What would I see on an equivalent place where you live?

This lady was carefully dusting every opening of a rooftop railing inside a garden in Shanghai. As tourists and other visitors walked beneath her, she continued cleaning. I immediately thought of the people we had seen sweeping the side of major highways with brooms. What might this possibly say about China’s employment or interest in cleanliness or care of public areas? What would I see on an equivalent place where you live?

I know I have possibly said too much about”western” and traditional (squat style) toilets in China. This sign was on the door to one stall where there was a western, seated style toilet. What does it tell you?

I know I have possibly said too much about”western” and traditional (squat style) toilets in China. This sign was on the door to one stall where there was a western, seated style toilet. What does it tell you?

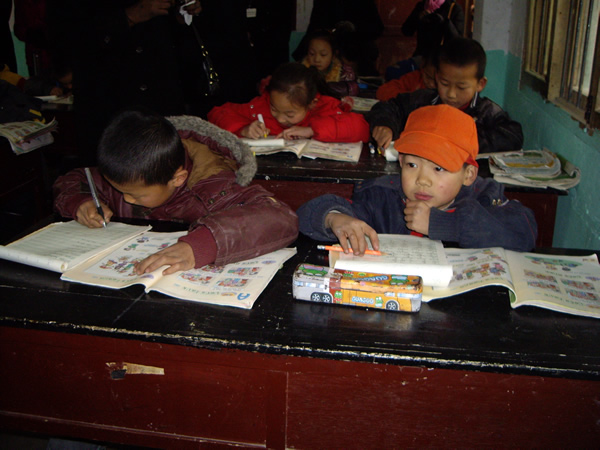

The library at the village school we visited had these books on the shelves. All the bookshelves were arranged in single layer displays of books like this. What can you tell about the school and the library? What would we learn from looking at the details of your school or town library?

The library at the village school we visited had these books on the shelves. All the bookshelves were arranged in single layer displays of books like this. What can you tell about the school and the library? What would we learn from looking at the details of your school or town library?

Speaking of libraries, in the brand new private school we visited in Shanghai, I saw students taking off their shoes to enter the school library. They lined them up neatly under the bench outside the library door, then went in. What might this say about libraries, shoes, or…? For what places do you take your shoes off?

Speaking of libraries, in the brand new private school we visited in Shanghai, I saw students taking off their shoes to enter the school library. They lined them up neatly under the bench outside the library door, then went in. What might this say about libraries, shoes, or…? For what places do you take your shoes off?

In the ancient and older buildings of the Forbidden City, a Buddhist temple in Xi’an, and the beautiful garden home (now museum) of an affluent Shanghai family, we saw elevated door sills that our guide said were designed to keep the evil spirits out. You have to step up over every door sill that goes to the outdoors. What do architectural features — even in non-religious buildings– reveal about the beliefs of people? What architectural features are common in your town’s buildings, and why are they there?

In the ancient and older buildings of the Forbidden City, a Buddhist temple in Xi’an, and the beautiful garden home (now museum) of an affluent Shanghai family, we saw elevated door sills that our guide said were designed to keep the evil spirits out. You have to step up over every door sill that goes to the outdoors. What do architectural features — even in non-religious buildings– reveal about the beliefs of people? What architectural features are common in your town’s buildings, and why are they there?

This photo from the Forbidden City shows another architectural feature we saw in many, many, places in China. Can you find out what these rooftop animals mean? Do you have any decorations that have meaning on the buildings in your city or country?

This photo from the Forbidden City shows another architectural feature we saw in many, many, places in China. Can you find out what these rooftop animals mean? Do you have any decorations that have meaning on the buildings in your city or country?

Right outside the Forbidden City is Ti’ananmen Square. This light pole has more than lights. What else do you see? Why is it there? What would we see on the utility poles in public areas where you live —-and why?

Right outside the Forbidden City is Ti’ananmen Square. This light pole has more than lights. What else do you see? Why is it there? What would we see on the utility poles in public areas where you live —-and why?

The necessities of everyday life take up time and effort in every culture. What does this street photo tell you about the people of Shanghai? Actually, we saw this in every city. How do people where you live handle the same tasks? (Please pardon the blurriness. This was taken through a bus window.)

The necessities of everyday life take up time and effort in every culture. What does this street photo tell you about the people of Shanghai? Actually, we saw this in every city. How do people where you live handle the same tasks? (Please pardon the blurriness. This was taken through a bus window.)

Play is important for children everywhere. This little boy had one rollerblade while his sister wore the other. They were playing outside the front door of their village home during the two hour break when children went home from school for lunch. What does this tell you about Chinese village children? If we watched children play in your neighborhood, what would we learn?

Play is important for children everywhere. This little boy had one rollerblade while his sister wore the other. They were playing outside the front door of their village home during the two hour break when children went home from school for lunch. What does this tell you about Chinese village children? If we watched children play in your neighborhood, what would we learn?

In the same small village, we saw this sign. What does it say about what is important there? What would we see in road signs (even on roads like this with few cars) where you live — and why?

In the same small village, we saw this sign. What does it say about what is important there? What would we see in road signs (even on roads like this with few cars) where you live — and why?

Ceremonies and dances appear n every culture. This reenactment of a dance celebration from the Tang Dynasty was even more breathtaking when “stopped” by the camera. What ceremonies and rituals would strangers to your home find striking or surprising? Why do these ceremonies continue?

Ceremonies and dances appear n every culture. This reenactment of a dance celebration from the Tang Dynasty was even more breathtaking when “stopped” by the camera. What ceremonies and rituals would strangers to your home find striking or surprising? Why do these ceremonies continue?

People say, “You are what you eat,” and one of the first thing everyone asks about my visit to China is about the food. This street stall in the middle of a Beijing neighborhood was well-stocked on a chilly December afternoon. What kind of food would visitors see for sale where you live, and where would they have to go to find it? What does that say about the economy and transportation systems where you live?

People say, “You are what you eat,” and one of the first thing everyone asks about my visit to China is about the food. This street stall in the middle of a Beijing neighborhood was well-stocked on a chilly December afternoon. What kind of food would visitors see for sale where you live, and where would they have to go to find it? What does that say about the economy and transportation systems where you live?

If we are what we eat, what would people say about you? These dumplings held mysterious contents, prompting us to ask “what’s inside?” before we tried them. What foods would visitors ask about when they visited your home?

If we are what we eat, what would people say about you? These dumplings held mysterious contents, prompting us to ask “what’s inside?” before we tried them. What foods would visitors ask about when they visited your home?

Sometimes looking at the details reveals more questions than answers, but guessing and hypothesizing about culture from the outside details is as delightful as biting into it — and you discover some good stuff.

A twenty-something former student of mine recently shared with incredulous delight that she “gets paid to think.” Her obvious enjoyment of going to work every day and reading, writing, and talking about ideas is what made her a teacher’s dream. But her words reveal more than personal attributes or wise career choice. She describes a world where thinking is important enough to pay for. In our supply and demand world, what better foundation for a new vision of education?

A twenty-something former student of mine recently shared with incredulous delight that she “gets paid to think.” Her obvious enjoyment of going to work every day and reading, writing, and talking about ideas is what made her a teacher’s dream. But her words reveal more than personal attributes or wise career choice. She describes a world where thinking is important enough to pay for. In our supply and demand world, what better foundation for a new vision of education?