TeachersFirst is blessed with a wonderful team of reviewers. The challenge we face is maintaining a consistent voice among so many teacher-writers. This same challenge rises in any collaborative student project where each student writes a portion of the content. How do we maintain a voice and writing style that does not scream, “Listen to how different I am”? Of course, in the “real world,” there are editors handle this challenge, shifting sentences and wrangling words to conduct a song in unison without erasing the beautiful tone of each writer.

As I work with our team, I realize that the lessons I learn from these lifelong learners, our teacher/reviewer/writers, are similar to those any teacher learns from students. My lesson this week was on feedback. The editorial team decided to share screencasts of the editorial process with each reviewer. The screencasts follow the m ouse as the editor reads, mulls things over, makes changes, moves things, and –in effect–thinks “on screen.” It is stream of consciousness editing in real time. (That element of time matters.)

ouse as the editor reads, mulls things over, makes changes, moves things, and –in effect–thinks “on screen.” It is stream of consciousness editing in real time. (That element of time matters.)

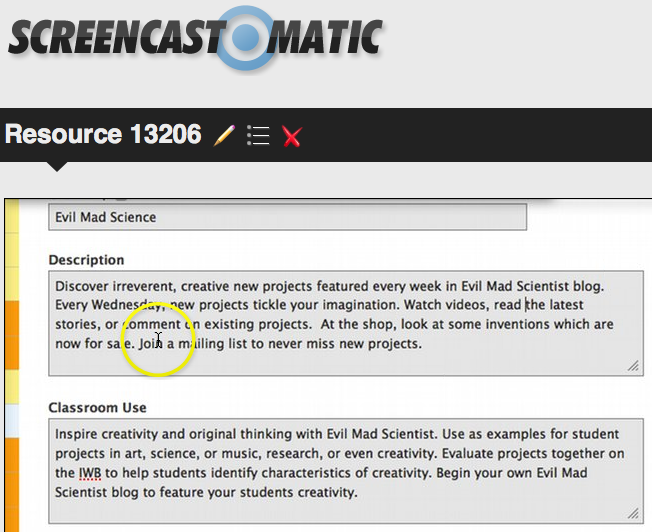

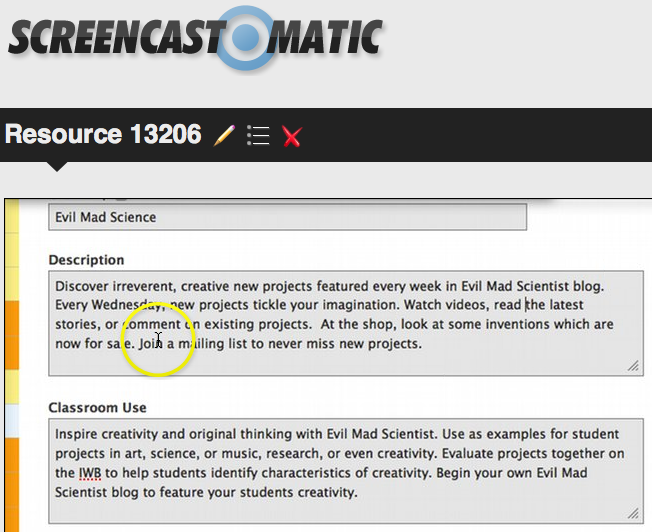

You could do the same: have a student “editor” (or you) use a tool like Screencastomatic (reviewed here) to record the process of revising a piece of writing. Another possible tool is Primary Pad (reviewed here) which plays changes back like a tape recorder. Keep it simple. Focus in on changing one to three things that writer needs most. Let him/her watch as you combine sentences to eliminate redundancy or add active verbs. Don’t TELL him, SHOW him. Don’t talk about it, just share the link and see what happens. Perhaps have a slightly more talented writer make a recording for one who is having trouble with a specific aspect of writing. As a precaution, retain a copy of the original, in case the writer feels robbed of his work.

In the case of our reviewers, the response was as authentic as the situation. The process has taught me a lot about how we learn as writers. My fear going into this was that we would violate the very personal ownership that writers feel. Instead, we are hearing excited feedback on the screencasts. Specifically, if the release of ownership is motivated and justified by a purpose (such as making a group project sound consistent or making our site more consistent), most writers will respond, analyzing what they observe about the changes at a level of metacognition any teacher would thrill to see:

As I looked at the screencast last night, I do see more what you mean in past feedback and what you are looking for…. I am making a list of the words, phrases to stay away from as well as use as examples to be a better writer. The screencast was actually much better feedback than just…comments. I really appreciated having that.

—–

I LOVE this, thank you for doing it! It is so helpful for me to get a better idea …. Based on what I see, more of my sentences should start with verbs – making them have more of an active voice and I’ll definitely try to combine sentences more effectively.

—–

The screencast is a lot more effective than the mark up on a word doc, I think! It’s like, real time, or something.

This feedback on our feedback is enough to put screencasting high on my list as a powerful tool. Whether we respond to professional work, student lab reports, stories, or essays, we can offer an authentic, real-time window into revision and writing. And it takes a LOT less time than writing up all those comments … or reading this lengthy post!

I learn from what I see. Yes, there are a few students who throw a few text boxes onto a computer screen like fill-in-the-blanks on a worksheet and call it an infographic. But so many more have made steady progress from a few images on a rectangle (their first attempt) to a carefully color coordinated arrangement of words, images, and lines/arrows that explain photosynthesis or DNA replication (attempts 2 and 3). As a set of fresh eyes, looking from a distance instead of from the teacher’s desk in the bio lab, I see understanding. I see science concepts I had long forgotten, now freshly explained to me by a 9th grader. I make comments on their wiki because they need to know that their work makes sense. I also make suggestions (no teacher can ever resist a chance!).

I learn from what I see. Yes, there are a few students who throw a few text boxes onto a computer screen like fill-in-the-blanks on a worksheet and call it an infographic. But so many more have made steady progress from a few images on a rectangle (their first attempt) to a carefully color coordinated arrangement of words, images, and lines/arrows that explain photosynthesis or DNA replication (attempts 2 and 3). As a set of fresh eyes, looking from a distance instead of from the teacher’s desk in the bio lab, I see understanding. I see science concepts I had long forgotten, now freshly explained to me by a 9th grader. I make comments on their wiki because they need to know that their work makes sense. I also make suggestions (no teacher can ever resist a chance!). I email their teacher to ask– does she have any idea how GOOD her students’ work really is? Can she reflect from afar to gain perspective? Or does February have her so earthbound that she cannot see the big picture from above?

I email their teacher to ask– does she have any idea how GOOD her students’ work really is? Can she reflect from afar to gain perspective? Or does February have her so earthbound that she cannot see the big picture from above?