My something impossible: Creative school

I have enjoyed reading Shelly Blake-Plock’s 2009 predictions of 21 things that will be obsolete by 2020 and subsequent response to his naysayers (March, 2011). Although I have some doubts about the optimism of some of the predictions, I find myself singing along with several of the ideas. Certainly most of us — even those who advocate for leveraging the power of technology for new ways of teaching and learning– have our doubts about whether education can change that much that fast, but the rhythm beating inside these predictions is that today’s technological change is not just gadgets:

we’re not talking about computers anymore. We’re talking about the way that we connect to one another as human beings.

We’re also talking about how we connect to our own creative, thoughtful selves. I recall a day in the early 1990s when one of our local school board members refused to enter the brand new computer lab at one of the elementary schools where I taught. His boastfully stated reason: “I will not enter that room because no learning takes place there.” While I know there were many poor uses of that lab, it happened to be the place where I witnessed a remarkable transformation just weeks later. I watched a fourth grader (call him Randy) discover Hyperstudio (v.1 or 2, I think) and simply go crazy. For the next four months until school got out, Randy spent every moment he could weasel to sit at that computer ad create a Hyperstudio stack about … well, honestly, I don’t remember which animal it was. That stack lead to another and another. Teachers had to require Randy to go out for recess. The principal would stop by to suggest that sunshine was important. By the end of fifth grade, fed by a brand new, dial-up Internet connection at his home, Randy had taught himself HTML and was teaching others. By the end of ninth grade, he had taken all the cast-off, painfully slow PCs he could gather from trash cans and built his own supercomputer in a high school storage closet. The custodians rolled their carts down the hall past Randy in that warm, unventilated closet, stringing cat-5 cable he had snagged from who-knows-where. By the time he finished two years of undergrad, Randy was spending the summer at Los Alamos doing research. All of this started from being able to create. I saw it happen.My favorite verse from Blake-Plock’s song, however, is this powerful charge to all of us. I want to sing this from electronic rooftops:

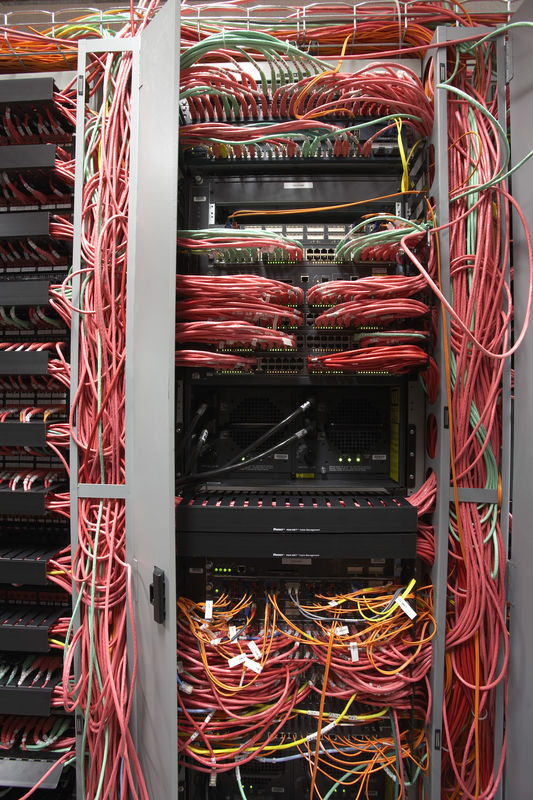

Randy spent every moment he could weasel to sit at that computer ad create a Hyperstudio stack about … well, honestly, I don’t remember which animal it was. That stack lead to another and another. Teachers had to require Randy to go out for recess. The principal would stop by to suggest that sunshine was important. By the end of fifth grade, fed by a brand new, dial-up Internet connection at his home, Randy had taught himself HTML and was teaching others. By the end of ninth grade, he had taken all the cast-off, painfully slow PCs he could gather from trash cans and built his own supercomputer in a high school storage closet. The custodians rolled their carts down the hall past Randy in that warm, unventilated closet, stringing cat-5 cable he had snagged from who-knows-where. By the time he finished two years of undergrad, Randy was spending the summer at Los Alamos doing research. All of this started from being able to create. I saw it happen.My favorite verse from Blake-Plock’s song, however, is this powerful charge to all of us. I want to sing this from electronic rooftops:

Teachers: you are the most amazing people on the planet. You are gifted with a fine mind and great compassion. You handle adversity and trauma and you inspire the future. You are going to have to be the ones to figure this out. You can’t rely on your administrators to do this for you. They are busy. They don’t always see what’s going on or what’s available. So you’ve got to make it happen.

My optimistic prediction by 2020: Creative School. Creative in the same three ways Randy modeled:

- Creative for students. The impulse to create is closely followed by the impulse to share. With technology changing “the way that we connect to one another as human beings” and facilitating creative process, school becomes a place where learning IS creating. Randy wanted to share via Hyperstudio, and share he did!

- Creative in making do with whatever you can find. If you don’t have a lot of technology, use what you do have. Kids are very good at that, if given permission to put things together, problem-solve, and experiment. My one caveat is that there needs to be an Internet connection in there somewhere. If they have to schedule ways to share it or find ways to network it, they will, especially if teachers band together to do the same (we did it in the early days of Internet). As Blake-Plock says, “You are going to have to be the ones to figure this out.” Luckily, kids like Randy are on the team.

- Creative in looking at things another way. If we think we have delineated the “replicable model” for “21st century learning,” anyone who really gets it laugh at us. The whole point is that things change too fast. The dream model needs to be built upon creative flexibility. Randy saw throw-away computers as new opportunities. If kids don’t learn one way or the learning they need to survive changes, we immediately change routes. All of us need to be nimble thinkers.

I am often accused of being idealistic. I figure after 27 years in classrooms, I can be as idealistic as I want to be. I have earned it through years of seeing it all. I hope I am seeing clearly as I look to 2020: the era of Creative School.